Beyond the beautiful tribal portraits lies an experience so profound that many travelers return again and again. I’ve recently returned from 35 days in Ethiopia’s Omo Valley, a place I’ve visited multiple times a year for more than 15 years. Still, the depth of tradition, the ceremonies, and the photographic opportunities continue to overwhelm me. Each visit reveals something new: a moment of quiet preparation, a celebration unfolding in rhythm and dust, a gesture or expression that carries generations of meaning. This is a world that welcomes you gently, shaped by years of shared moments, understanding, and genuine connection.

I am still in awe of the tribal ceremonies that have continued even as the modern world has been placed in their hands. The rhythm, energy, and meaning within these traditions remain as powerful as ever expressions of identity that carry generations of history. Each ceremony feels like stepping into a living story, one that reminds me how resilient and deeply rooted these cultures are.

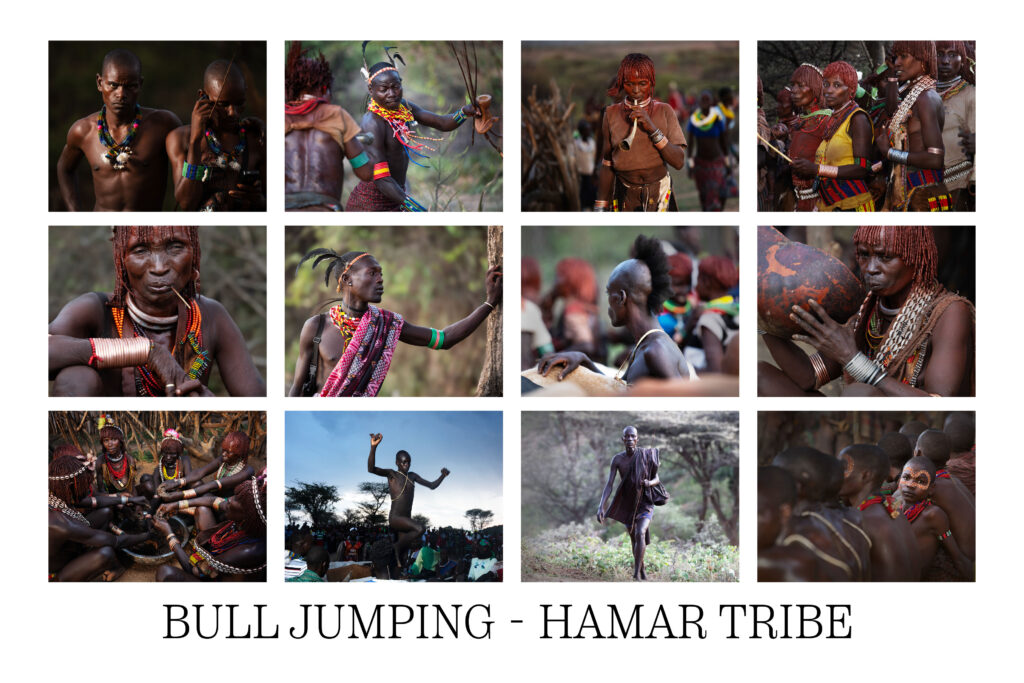

The Hamar bull-jumping ceremony is a symbolic coming-of-age ritual, marking a young man’s transition from boyhood into adulthood. The day begins long before the jump itself, as family members and entire villages gather in vibrant anticipation. Women, sisters, cousins, and close relatives adorn themselves with beadwork, iron bracelets, and ochre. Their singing and rhythmic movement create an emotional pulse that carries through the ceremony. The sound of horns, rattles, and chanting fills the air, honoring both heritage and the weight of the moment ahead.

As the sun lowers, the young man is led toward a line of bulls. Surrounded by layers of tradition, he must run across their backs four times without falling, a feat that symbolizes readiness for responsibility, leadership, and marriage. The atmosphere is charged with emotion: pride, tension, and the deep bonds of family and community. Elders watch closely, offering guidance and blessing, while the women continue their songs, voices rising in powerful, unwavering support.

The Dimi Ceremony is one of the most striking and symbolic rites of passage. Held for the first-born daughters of Daasanach families, it marks her transition into womanhood and her eligibility for marriage. But more than that it’s a celebration of lineage, legacy, and the strength of community.

Fathers and male relatives wear elaborate ochre body paint, leopard skins, and towering wigs crafted from ostrich feathers. They carry ceremonial staffs and sing ancestral songs in a slow, measured procession. The women gather in a circle, draped in leather garments and beads, their bodies swaying to the rhythm of memory. It’s emotional and powerful. Grounded. Ancient. As though time has stood still.

The Donga is one of the most dramatic and emotionally charged rites of passage among the Suri. Far more than a competition, it is a test of courage, discipline, resilience, and identity. Young men prepare for weeks, sometimes months, gathering in the cattle camps to practice footwork, sharpen their reflexes, and strengthen their bodies. On the day of the ceremony, warriors arrive coated in ash or clay, their bodies adorned with striking yet straightforward natural pigments, each mark carrying its own meaning. The men all hum and sing with anticipation as they step into the ring, surrounded by their clans, elders, and families who watch in unified silence.

When the fighting begins, it is fast, controlled, and intensely physical. Sticks crack through the air, dust rises beneath their feet, and each movement is a blend of instinct and trained precision. Despite its fierce appearance, the Donga is bound by respect; fighters are expected to show restraint. Once victory is declared, it is celebrated between the fighters with a bond of brotherhood and pride. For the Suri, this ritual is not merely a display of strength; it is a pathway to maturity, honor, and social standing within the community. When the dust finally settles, the ceremony leaves a lasting impression of raw power tempered by deep cultural meaning, an ancient tradition that continues to live at the heart of Suri identity.

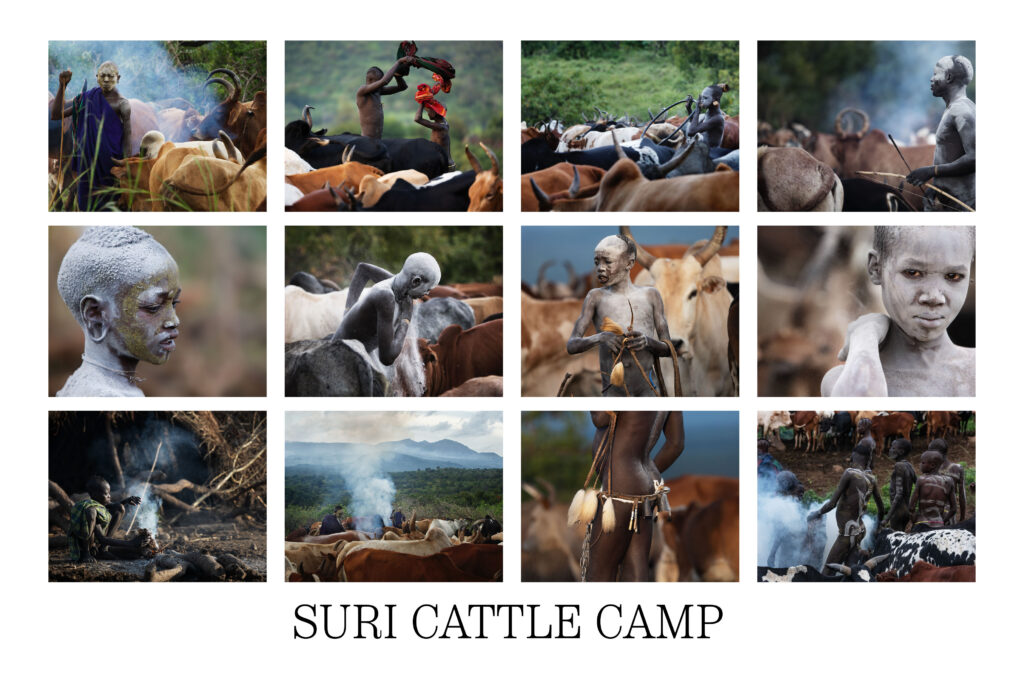

The Suri cattle camps are atmospheric places a world shaped by dust, smoke, and the sound of cattle moving slowly through the early light. At dawn, a soft haze rises from the smoldering dung fires used to protect both people and animals from insects. Young warriors move with quiet purpose, coating their bodies in ash or clay, creating patterns that are part protection, part expression. Soon, the cattle are led to the fields for grazing and to the river for water. Returning in the late afternoon, the camp once again comes to life, and the rituals begin again. The connection between the Suri and their cattle is unmistakable; these herds represent wealth, history, and identity, and the rhythm of camp life revolves entirely around their care.

I just returned from Northern Kenya on an exploratory trip with the Mackay Africa team. The tribal cultures there flow seamlessly down from Ethiopia, carrying the same depth of tradition found in the Omo Valley. Being there again reminds me just how rich and diverse this entire cultural corridor is and why I’m so passionate about sharing these experiences in a meaningful, respectful way.

The Signature Best of the Omo in 2027 is open for registration!! . Read all the details!